The Isostatic Role of Orogeny: Mountains as Lithospheric Anchors

The geological significance of mountain ranges extends far beneath the visible topography of the Earth’s surface. Modern geophysics and plate tectonics have revealed that mountains are not merely piles of accumulated rock sitting atop the crust, but are deeply rooted structures that play a critical role in maintaining the mechanical and gravitational equilibrium of the lithosphere. This article explores the concept of isostasy, the Airy-Heiskanen model of crustal thickness, and the “root” systems of mountains that function analogously to pegs or anchors, stabilizing the Earth’s continental plates.

Introduction: The Hidden Depth of Mountains

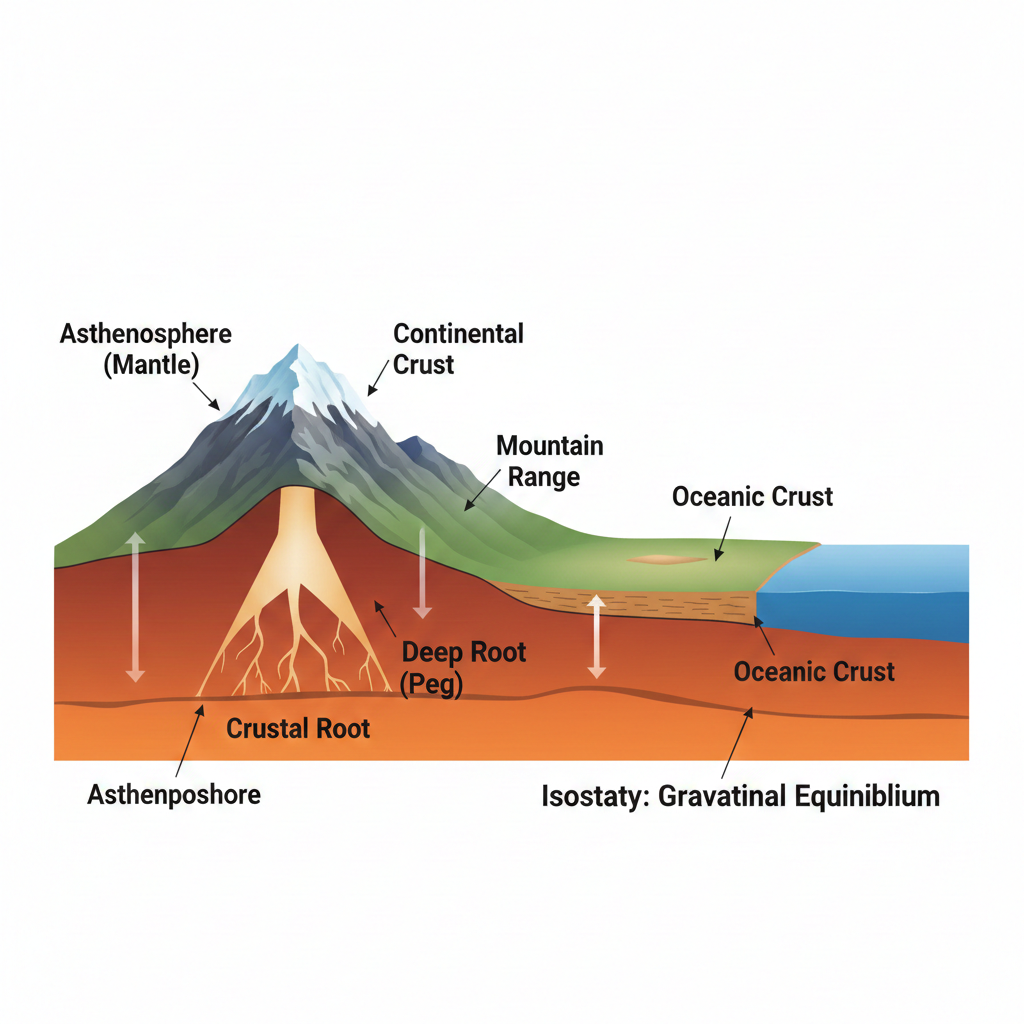

To the casual observer, a mountain range like the Himalayas or the Alps is a feature of height. However, to a geophysicist, a mountain is primarily a feature of depth. The principle of buoyancy dictates that for every significant elevation above sea level, there must be a corresponding “root” penetrating deep into the denser mantle below.

This structural reality is essential for the stability of the Earth’s crust. Without these deep roots, the continental crust—which is significantly thicker and less dense than the oceanic crust—would lack the structural integrity required to withstand the immense tectonic forces generated by planetary rotation and mantle convection.

1. The Principle of Isostasy

The primary scientific framework for understanding mountains as “pegs” is Isostasy (from the Greek isostasios, meaning “in equal standing”).1 Isostasy describes the state of gravitational equilibrium between the Earth’s lithosphere and asthenosphere.2

The Airy-Heiskanen Model

Proposed by Sir George Airy in 1855, this model suggests that the Earth’s crust is a more buoyant shell floating on a more fluid, denser substratum (the mantle).3 Airy hypothesized that just as a large iceberg must have a deep underwater section to support its height above water, mountains must have deep roots of low-density crustal material extending into the denser mantle.

In this model:

- High mountains possess deep roots that act as anchors.4

- Low plains have much shallower roots.

- The relationship between the height and the depth of the root can be calculated based on the density of the crust and the mantle.

This equation demonstrates that the “peg” or “root” is often several times deeper than the mountain is high. For example, the Everest peak (approx. 8.8 km) is supported by a crustal root that extends over 70 km into the Earth.

2. Orogeny and Lithospheric “Pegging”

The process of mountain building, or orogeny, occurs primarily at convergent plate boundaries.5 When two continental plates collide, the crust undergoes intense compression, folding, and faulting.6

Mechanical Stabilization

Mountains function as pegs in a mechanical sense by “locking” continental masses. During subduction or collision, the downward projection of the mountain root into the mantle increases the frictional resistance between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere. This effectively anchors the continental plate, preventing it from sliding erratically over the semi-fluid mantle.

The “Nail” Analogy in Geophysics

In many geophysical texts, the term “root” is the standard nomenclature. However, the functional description often mirrors that of a peg or a nail. The root provides lateral stability. If the Earth’s crust were of uniform thickness, the centrifugal forces of the Earth’s rotation would exert different stresses on the landmasses, potentially leading to greater tectonic instability. The distribution of mountain ranges and their deep roots acts as a counter-balance system.

3. Case Study: The Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau

The Himalayas serve as the premier example of the “peg” function. Geoseismic imaging has confirmed that the Tibetan Plateau is supported by a crustal thickness nearly double the global average.

Recent studies using S-wave tomography have mapped these roots with high precision. These studies show that the Indian plate is not just colliding with the Eurasian plate but is actually being “wedged” underneath it, creating a massive, deep-seated anchor that stabilizes the entire region’s geography despite the immense pressure of the collision.

4. Theological Parallel: The Quranic Insight

In the field of “Theological Geophysics,” scholars often point to the striking linguistic and conceptual parallels between modern isostasy and the Quranic description of mountains.

The Quran describes mountains using the Arabic word “Awtad” (plural of Watad), which literally translates to “pegs” or “stakes” (such as those used to anchor a tent).7

“Have We not made the earth as a bed, and the mountains as pegs?” (Quran, 78:6-7)

Furthermore, the Quran describes the function of these mountains as preventing the Earth from shaking:8

“And He has set up on the earth mountains standing firm, lest it should shake with you…” (Quran, 16:15)

From a scientific perspective, this “shaking” can be interpreted as the lithospheric instability that would occur if the crust lacked its deep, anchoring roots. Before the development of the theory of plate tectonics and the discovery of mountain roots via seismic waves in the 20th century, the idea that mountains had “peg-like” extensions deep underground was unknown to science.

The use of the word Awtad is particularly precise: a peg is characterized by having a small portion visible above the surface while the majority of its body is driven into the ground to provide stability. This mirrors the Airy model of isostasy perfectly, where the mountain root is significantly larger than the visible peak.

Read also The Protective Atmosphere. And Human Embryonic Development stages. Heaven and Earth were one.

Conclusion

The function of mountains is dual-natured: they are the majestic peaks that influence global climate and ecosystems, but they are also the silent, deep-seated anchors of the continents. Through the principle of isostasy, we understand that mountains are “pegs” that balance the Earth’s crust against the fluid mantle, ensuring a level of geological stability essential for life. The correlation between ancient scripture and modern geophysics remains a subject of profound interest for those studying the intersection of science and religion.

Scientific References

- Watts, A. B. (2001). Isostasy and Flexure of the Lithosphere. Cambridge University Press.9 This authoritative text provides the mathematical foundation for how mountain roots support topography.

- Heiskanen, W. A., & Moritz, H. (1967). Physical Geodesy. W.H. Freeman and Company.10 A foundational source on the Earth’s gravitational field and the Airy-Heiskanen model.